Mary Gregory guest post

Explaining early years mental health

Early years mental health refers to the first 4 years of a child’s life. Read a guest blog post by Mary Gregory, Clinical Psychologist and PhD Candidate, to find out what impact negative experiences during this time can have on a child later in life, and what we can do to set children up for success.

Mary Gregory is a proud mother of two daughters and a Clinical Psychologist who runs a telehealth based private practice PsychHelp.

Mary is in the final year of her PhD examining an online parenting program BetterBonds at the University of the Sunshine Coast (USC).

Research has made it clear that the early years has a large impact on later health and wellbeing. This is a period when the structures and neuronal pathways of the brain are being created.

This is an important life phase as the building blocks for later mental health are being established during this time period.

Within this age group there are two themes which are particularly important to consider the attachment between the baby and their primary caregivers, and whether they experience adverse events.

Whenever we consider this age group it is most important to understand that you are not assessing or treating an individual infant or toddler it is always the child AND someone else.

The someone else may be a parent, kin carer or foster carer.

This can be expanded to include a community, environment, social services, and health services.

Mental health problems in this age group occur within a system of relationships as is likely the case at all age ranges.

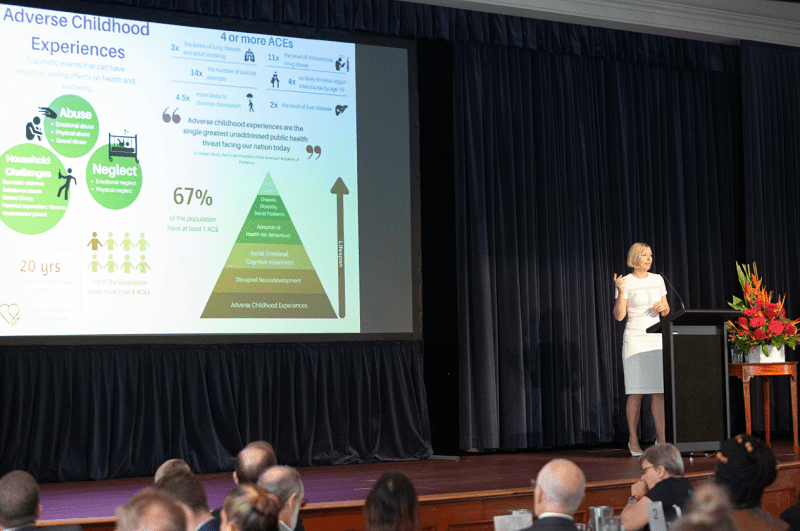

The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACES) was a major study of over 17,000 people in Southern California.

From this study we learned that adverse experiences during these early years are related to a range of mental health and physical health problems later in life as well as unhelpful coping behaviours.

What the ACES research showed is that adverse events such as having a parent who has mental health problems, abused you physically, sexually or emotionally, used drugs or drank too much, went to prison or made you feel unloved is related to adverse health outcomes later in life.

Each one of these types of events provides a score of one up to a possible 10.

The researchers concluded that “rebalancing expenditure towards ensuring safe and nurturing childhoods would be economically beneficial and relieve pressures on health-care systems”.

It is important to understand that a reduction in ACES would not only be economically beneficial it would also save a lot of people from having to live sad and scary lives.

As a Clinical Psychologist I have worked with a number of clients who brought to life the ACEs research as well as vividly portraying the importance of attachment theory.

For the purposes of this article I would like to introduce Melissa.

Melissa is actually a combination of a number of my clients who I think deserve a voice in forums such as this.

When I first moved to Australia, I worked with adults who had serious mental health concerns.

One of my first clients was Melissa; some readers may have met, worked with or been someone like her.

She had serious mental health concerns, physical health concerns and a lot of unhelpful coping behaviours.

She was involved with the Police Service, the Ambulance Service, the Health Service, Centrelink, Child Safety as her child had been removed, Department of Housing, and Probation.

Everyone was doing their best including Melissa herself.

Melissa’s ACE score was high, probably an 8 or 9.

Her childhood involved sexual, physical and emotional abuse by family and then later by peers.

She never had a close relationship with any parent or caregiver and had been in and out of child safety care during her teenage years.

Melissa was miserable and we did our best to work together to manage her situation.

Fast forward to my next position at a child mental health service, where I met another Melissa who was 12 years old.

Her ACE score was also already at an 8 out of a possible 10, meaning she had experienced many adverse events in her short life.

There had already been multiple removals by Child Safety from her family and many people in her family experienced serious mental health problems.

She had never had any attachment to a safe or secure caregiver and was also miserable the majority of the time.

Now in my time at the child mental health service I did not meet a Melissa in the 0-4 age range.

My question for you is why? Did I meet her, and not realise the seriousness of her situation? Possibly.

Was she attending another service? Possibly.

However, my belief is that 2 year old Melissa is being missed until she is old enough to display behaviours of notice.

I think I did see Melissa in the waiting room, a younger sister of a troubled young person, but she was not referred to me or did not meet the criteria for help yet.

To me this is why giving young people the best start in life during these early years is so important, because we are missing these babies.

We know that a secure attachment can provide resilience against stressors and that a lack of a secure attachment is correlated with a range of difficulties later in life.

We know that the more adverse childhood events a child experiences the worse their mental and physical health outcomes are.

This is the age range we need to be focusing our resources on.

I hope by the time my career ends there will be more effective prevention measures in place and children in Melissa’s situation will not live such traumatic lives.

We know a lot to help us with this goal, we know a secure attachment provides resilience against life stress and we know new parents need support.

Having small children myself, I know new parents need A LOT of support.

We know for a child to have a secure attachment which is a protective factor providing resilience they need sensitive, cooperative, available and accepting parents or caregivers.

We need programs which focus on building relationships, connections and bonds whose main goal is to foster love.

My belief is that it is through innovation and the use of new technologies that more families will be reached.

We need assessments to identify Melissa before she is even born.

We need to make services for new parents easily accessible and free.

The results from my PhD research have demonstrated how little time parents have and how much programs need to incorporate the reality that often the only time parents have is when their baby has a short nap.

We need a range of programs that fit with the range of difficulties new parents face.

We need to support parents who have mental illness.

We need to reach out to Dad’s, Grandparents, Aunties and Uncles, and foster carers and ensure they are included in the process and services can support them as well.

We need to teach parents about attachment, so they realise the importance of the relationship they build with their child.

One last point, I want to acknowledge all the great work of all mental health professionals.

I am sure many people reading this will have worked with someone like Melissa or Melissa’s parents or prevented a family from deteriorating to this point.

I think any acknowledgement of the many lives who are saved or improved by our work is incredibly important because it helps us keep going when we are often up against financial and organisational barriers.

Support for parents and young children

Parentline 1300 30 1300 https://www.parentline.com.au/

Playgroup Qld https://www.playgroupqld.com.au/

Triple P Parenting Program https://www.triplep-parenting.net.au/qld-uken/triple-p/

Raising Children Network https://raisingchildren.net.au/

Australian Association for Infant Mental Health https://www.aaimhi.org/

Peach Tree Perinatal: https://peachtree.org.au/

Better Bonds free online program: https://betterbonds.com.au/

University of Sunshine Coast Clinical Trials: https://www.usc.edu.au/trials

PsychHelp: https://psychhelp.com.au